Meaning (noun.)

Definition: The perceived significance, understanding, or importance of something.

Also referenced as: Mean (verb) Means (verb) Meanings (noun) Meant (verb)

Related to: Fuzzy, Homograph, Interpretation, Language, Misunderstandings, Myths, Perception, Sense Making, Stakeholder, Subjective, Understand, User

Chapter 1: Identify the Mess | Page 18

Knowledge is complex.

Knowledge is surprisingly subjective.

We knew the earth was flat, until we knew it was not flat. We knew that Pluto was a planet until we knew it was not a planet.

True means without variation, but finding something that doesn’t vary feels impossible.

Instead, to establish the truth, we need to confront messes without the fear of unearthing inconsistencies, questions, and opportunities for improvement. We need to be open to the variations of truth that are bound to exist.

Part of that includes agreeing on what things mean. That’s our subjective truth. And it takes courage to unravel our conflicts and assumptions to determine what’s actually true.

If other people have a different interpretation of what we’re making, the mess can seem even bigger and more hairy. When this happens, we have to proceed with questions and set aside what we think we know.

Chapter 1: Identify the Mess | Page 21

Information is not data or content.

Data is facts, observations, and questions about something. Content can be cookies, words, documents, images, videos, or whatever you’re arranging or sequencing.

The difference between information, data, and content is tricky, but the important point is that the absence of content or data can be just as informing as the presence.

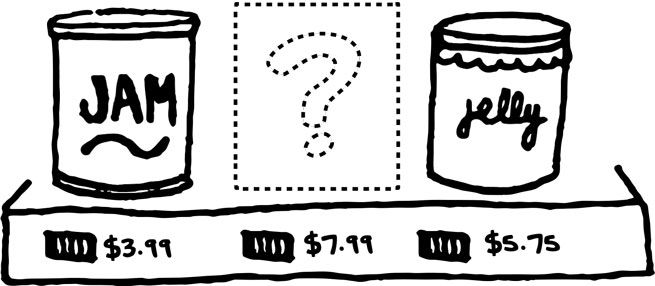

For example, if we ask two people why there is an empty spot on a grocery store shelf, one person might interpret the spot to mean that a product is sold-out, and the other might interpret it as being popular.

The jars, the jam, the price tags, and the shelf are the content. The detailed observations each person makes about these things are data. What each person encountering that shelf believes to be true about the empty spot is the information.

Chapter 1: Identify the Mess | Page 26

To do is to know.

Knowing is not enough. Knowing too much can encourage us to procrastinate. There’s a certain point when continuing to know at the expense of doing allows the mess to grow further.

Practicing information architecture means exhibiting the courage to push past the edges of your current reality. It means asking questions that inspire change. It takes honesty and confidence in other people.

Sometimes, we have to move forward knowing that other people tried to make sense of this mess and failed. We may need to shine the light brighter or longer than they did. Perhaps now is a better time. We may know the outcomes of their fate, but we don’t know our own yet. We can’t until we try.

What if turning on the light reveals that the room is full of scary trolls? What if the light reveals the room is actually empty? Worse yet, what if turning on the light makes us realize we’ve been living in darkness?

The truth is that these are all potential realities, and understanding that is part of the journey. The only way to know what happens next is to do it.

Chapter 2: State your Intent | Page 33

What is good?

Language is any system of communication that exists to establish shared meaning. Even within a single language, one term can mean something in situation A and something different in situation B. We call this a homograph. For example, the word pool can mean a swimming pool, shooting pool, or a betting pool.

Perception is the process of considering, and interpreting something. Perception is subjective like truth is. Something that’s beautiful to one person may be an eyesore to another. For example, many designers would describe the busy, colorful patterns in the carpets of Las Vegas as gaudy. People who frequent casinos often describe them as beautiful.

However good or bad these carpet choices seem to us, there are reasons why they look that way. Las Vegas carpets are busy and colorful to disguise spills and wear and tear from foot traffic. Gamblers likely enjoy how they look because of an association with an activity that they enjoy. For Las Vegas casino owners and their customers, those carpet designs are good. For designers, they’re bad. Neither side is right. Both sides have an opinion.

What we intend to do determines how we define words like good and bad.

Chapter 2: State your Intent | Page 34

Good is in the eye of the beholder.

What’s good for a business of seven years may not work for a business of seven weeks. What works for one person may be destructive for another.

When we don’t define what good means for our stakeholders and users, we aren’t using language to our advantage. Without a clear understanding of what is good, bad can come out of nowhere.

And while you have to define what good means to create good information architecture, it’s not just the architecture part that needs this kind of focus.

Every decision you make should support what you’ve defined as good: from the words you choose to the tasks you enable, and everything in between.

When you’re making decisions, balance what your stakeholders and users expect of you, along with what they believe to be good.

Chapter 2: State your Intent | Page 37

Meaning can get lost in translation.

Did you ever play the telephone game as a child?

It consists of a group of kids passing a phrase down the line in a whisper. The point of the game is to see how messed up the meaning of the initial message becomes when sent across a messy human network.

Meaning can get lost in subtle ways. It’s wrapped up in perception, so it’s also subjective. Most misunderstandings stem from mixed up meanings and miscommunication of messages.

Miscommunications can lead to disagreements and frustration, especially when working with others.

Getting our message across is something everyone struggles with. To avoid confusing each other, we have to consider how our message could be interpreted.

Chapter 2: State your Intent | Page 38

Who matters?

The meaning we intend to communicate doesn’t matter if it makes no sense, or the wrong sense, to the people we want to reach.

We need to consider our intended users. Sometimes they’re our customers or the public. Often times, they’re also stakeholders, colleagues, employees, partners, superiors, or clients. These are the people who use our process.

To determine who matters, ask these questions:

Chapter 2: State your Intent | Page 45

Meet Karen.

Karen is a product manager at a startup. Her CEO thinks the key to launching their product in a crowded market is a sleek look and feel.

Karen recently conducted research to test the product with its intended users. With the results in hand, she worries that what the CEO sees as sleek is likely to seem cold to the users they want to reach.

Karen has research on her side, but she still needs to define what good means for her organization. Her team needs to state their intent.

To establish an intent, Karen talks with her CEO about how their users’ aesthetic wants don’t line up with the look and feel of the current product.

She starts their conversation by confirming that the users from her research are part of the intended audience for the product.

Next, she helps the CEO create a list of questions and actions the research brought up.

Afterwards, Karen develops a plan for communicating her findings to the rest of the team.

Chapter 3: Face Reality | Page 52

Reality involves many factors.

No matter what you’re making, you probably need to consider several of these factors:

- Time: “I only have _____________________.”

- Resources: “I have _____________________.”

- Skillset: “I know how to ________________ , but I don’t know how to ______________ yet.”

- Environment: “I’m working in a ___________.”

- Personality: “I want this work to say _________ about me.”

- Politics: “Others want this work to say _________________ about ____________.”

- Ethics: “I want this work to do right by the world by __________________.”

- Integrity: “I want to be proud of the results of my work, which means _____________.”

Chapter 3: Face Reality | Page 78

Face your reality.

Everything is easier with a map. Let me guide you through making a map for your own mess.

On the following page is another favorite diagram of mine, the matrix diagram.

The power of a matrix diagram is that you can make the boxes collect whatever you want. Each box becomes a task to fulfill or a question to answer, whether you’re alone or in a group.

Matrix diagrams are especially useful when you’re facilitating a discussion, because they’re easy to create and they keep themselves on track. An empty box means you’re not done yet.

After making a simple matrix of users, contexts, players, and channels, you’ll have a guide to understanding the mess. By admitting your hopes and fears, you’re uncovering the limits you’re working within.

This matrix should also help you understand the other diagrams and objects you need to make, along with who will use and benefit from them.

Chapter 4: Choose a Direction | Page 100

Watch out for options and opinions.

When we talk about what something has to do, we sometimes answer with options of what it could do or opinions of what it should do.

A strong requirement describes the results you want without outlining how to get there.

A weak requirement might be written as: “A user is able to easily publish an article with one click of a button.” This simple sentence implies the interaction (one click), the interface (a button), and introduces an ambiguous measurement of quality (easily).

When we introduce implications and ambiguity into the process, we can unknowingly lock ourselves into decisions we don’t mean to make.

As an example, I once had a client ask for a “homepage made of buttons, not just text.” He had no idea that, to a web designer, a button is the way a user submits a form online. To my client, the word button meant he could change the content over time as his business changes.

Chapter 4: Choose a Direction | Page 103

Meet Rasheed.

Rasheed is a consultant helping the human resources department of a large company. They want to move their employee-training processes online.

Rasheed’s research uncovered a lot of language inconsistencies between how employees are hired and trained in various departments.

He always expects to account for departmental differences, but he fears this many similar terms for the same things will make for a sloppy system design.

Rasheed has a choice. He could document the terms as they exist and move on. Or he could take the time to find a direction that works for everyone.

He decides to group the terms by similar meanings and host a meeting with the departments to choose which terms should lead, and which ones should fall back.

During the meeting, Rasheed:

Chapter 4: Choose a Direction | Page 90

Understand ontology.

If we were to write a dictionary, we’d be practicing lexicography, or collecting many meanings into a list. When we decide that a word or concept holds a specific meaning in a specific context, we are practicing ontology.

Here are some examples of ontological decisions:

- Social networks redefining “like” and “friends” for their purposes

- The “folders” on a computer’s “desktop” you use to organize “files”

- The ability to order at a fast food chain by saying a number

To refine your ontology, all you need is a pile of sticky notes, a pen, and some patience.

- Find a flat or upright surface to work on.

- Write a term or concept that relates to your work on each sticky note.

- Put the sticky notes onto the surface as they relate to each other. Start to create structures and relationships based on their location.

Chapter 4: Choose a Direction | Page 94

Create a list of words you don’t say.

A controlled vocabulary doesn’t have to end with terms you intend to use. Go deeper by defining terms and concepts that misalign with your intent.

For the sake of clarity, you can also define:

- Terms and concepts that conflict with a user’s mental model of how things work

- Terms and concepts that have alternative meaning for users or stakeholders

- Terms and concepts that carry historical, political, or cultural baggage

- Acronyms and homographs that may confuse users or stakeholders

In my experience, a list of things you don’t say can be even more powerful than a list of things you do. I’ve been known to wear a whistle and blow it in meetings when someone uses a term from the don’t list.

Chapter 4: Choose a Direction | Page 95

Words I don’t say in this eBook.

I’ve avoided using these terms and concepts:

- Doing/Do the IA (commonly misstated)

- IA (as an abbreviation)

- Information Architecture (as a proper noun)

- Information Architect (exceptions in my dedication and bio pages)

- App as an abbreviation (too trendy)

- Very (the laziest word ever)

- User experience (too specific to design)

- Metadata (too technical)

- Semantic (too academic)

- Semiotic (too academic)

I have reasons why these words aren’t good in the context of this book. That doesn’t mean I never use them; I do in some contexts.

Chapter 4: Choose a Direction | Page 96

Define terms for outsiders.

When I was in grade school, we did an assignment where we were asked to define terms clearly enough for someone learning our language. To define “tree” as “a plant that grows from the ground,” we first needed to define “plant,” “grow,” and “ground.”

It was an important lesson to start to understand the interconnectivity of language. I like to apply this kind of thinking in my work to uncover terms that are nested within other terms and their definitions.

- Write down the meaning of the term as simply as you can.

- Underline each term within your definition that needs to be further defined.

- Define those terms and test your definition with someone who doesn’t know those terms yet.

- Look at each individual word and ask yourself: What does this mean? Is it as simple as possible?

Chapter 4: Choose a Direction | Page 97

Understand the past.

As you talk through your controlled vocabulary, listen for stories and images people associate with each term.

Language has history. Synonyms and alternatives abound. Myths can get in your way too, unless you’re willing to uncover them.

Gather the following about each term:

- History: How did the term come into being? How has it changed over time?

- Myths: Do people commonly misunderstand this term, its meaning, or its usage? How?

- Alternatives: What are the synonyms for the term? What accidental synonyms exist?

When it comes to language, people are slow to change and quick to argue. Documenting these details will help you make your controlled vocabulary as clear and useful as possible.

Chapter 5: Measure the Distance | Page 110

Progress is as important to measure as success.

Many projects are more manageable if you cut them into smaller tasks. Sequencing those tasks can mean moving through a tangled web of dependencies.

A dependency is a condition that has to be in place for something to happen. For example, the links throughout this book are dependent on me publishing the content.

How you choose to measure progress can affect the likelihood of your success. Choose a measurement that reinforces your intent. For example:

Chapter 6: Play with Structure | Page 134

Humans are complex.

Tomatoes are scientifically classified as a fruit. Some people know this and some don’t. The tomato is a great example of the vast disagreements humans have with established exact classifications.

Our mental models shape our behavior and how we relate to information.

In the case of the tomato, there are clearly differences between what science classifies as a fruit and what humans consider appropriate for fruit salad.

If you owned an online grocery service, would you dare to only list tomatoes as fruit?

Sure, you could avoid the fruit or vegetable debate entirely by classifying everything as “produce,” or you could list tomatoes in “fruit” and “vegetables.”

But what if I told you that squash, olives, cucumbers, avocados, eggplant, peppers, and okra are also fruits that are commonly mistaken as vegetables?

What do we even mean when we say “fruit” or “vegetable” in casual conversations? Classification systems can be unhelpful and indistinguishable when you’re sorting things for a particular context.

Chapter 6: Play with Structure | Page 137

Taxonomies can be hierarchical or heterarchical.

When taxonomies are arranged hierarchically, it means that successive categories, ranks, grades, or interrelated levels are being used. In a hierarchy, a user would have to select a labeled grouping to find things within it. A hierarchy of movies might look like this:

- Comedies

- Romantic comedies

- Classic comedies

- Slap-stick comedies

Hierarchies tend to follow two patterns. First, a broad and shallow hierarchy gives the user more choices up front so they can get to everything in a few steps. As an example, in a grocery store, you choose an aisle, and each aisle has certain arrangement of products, but that’s as deep as you can go.

A narrow and deep hierarchy gives the user fewer choices at once. On a large website, like usa.gov, a few high level options point users to more specific items with each click.

When individual pieces exist on one level without further categorization, the taxonomy is heterarchical. For example, each lettered box in the arrangement in this illustration is heterarchical.

Chapter 7: Prepare to Adjust | Page 152

If it isn’t under the floorboards, it’s a façade.

Information architecture is like the frame and foundation of a building. It’s not a building by itself, but you can’t add the frame and foundation after the building is up. They’re critical parts of the building that affect the whole of it. Buildings without frames do not exist.

It’s hard to relay your intended meaning through façade alone. When your structure and intent don’t line up, things fall apart.

Imagine trying to open a fancy restaurant in an old Pizza Hut. The shape of its former self persists in the structure. The mid-nineties nostalgia for that brand is in its bones. Paint the roof; change the signage; blow out the inside; it doesn’t matter. The building insists, “I used to be a Pizza Hut.”

(Now type “used to be Pizza Hut” into Google’s image search and enjoy the laugh riot!)

Chapter 7: Prepare to Adjust | Page 153

We serve many masters.

No matter what the mess is made of, we have many masters, versions of reality, and needs to serve. Information is full of history and preconceptions.

Stakeholders need to:

- Know where the project is headed

- See patterns and potential outcomes

- Frame the appropriate solution for users

Users need to:

- Know how to get around

- Have a sense of what’s possible based on their needs and expectations

- Understand the intended meaning

It’s our job to uncover subjective reality.

An important part of that is identifying the differences between what stakeholders think users need and what users think they need for themselves.

Chapter 7: Prepare to Adjust | Page 157

This is hard.

It’s hard to decide to tear down a wall, take off the roof, or rip up the floorboards. It’s hard to admit when something architectural isn’t serving you.

It’s hard to find the words for what’s wrong.

It’s hard to deal with the time between understanding something is wrong and fixing it.

It’s hard to get there.

It’s hard to be honest about what went right and what went poorly in the past.

It’s hard to argue with people you work with about fuzzy things like meaning and truth.

It’s hard to ask questions.

It’s hard to hear criticism.

It’s hard to start over.

It’s hard to get to good.

Chapter 7: Prepare to Adjust | Page 160

Make sense yet?

- Have you explored the depth and edges of the mess that you face?

- Do you know why you have the intent you have and what it means to how you will solve your problem?

- Have you faced reality and thought about contexts and channels your users could be in?

- What language have you chosen to use to clarify your direction?

- What specific goals and baselines will you measure your progress against?

- Have you put together various structures and tested them to make sure your intended message comes through to users?

- Are you prepared to adjust?