Interact (verb.)

Definition: Act in such a way as to have an effect on another.

Also referenced as: Interaction (noun) Interacting (verb)

Related to: Ecosystem, Experience, Interface, Journey, Object, System, User

Chapter 1: Identify the Mess | Page 24

Users are complex.

User is another word for a person. But when we use that word to describe someone else, we’re likely implying that they’re using the thing we’re making. It could be a website, a product or service, a grocery store, a museum exhibit, or anything else people interact with.

When it comes to our use and interpretation of things, people are complex creatures.

We’re full of contradictions. We’re known to exhibit strange behaviors. From how we use mobile phones to how we traverse grocery stores, none of us are exactly the same. We don’t know why we do what we do. We don’t really know why we like what we like, but we do know it when we see it. We’re fickle.

We expect things to be digital, but also, in many cases, physical. We want things to feel auto-magic while retaining a human touch. We want to be safe, but not spied on. We use words at our whim.

Most importantly perhaps, we realize that for the first time ever, we have easy access to other people’s experiences to help us decide if something is worth experiencing at all.

Chapter 3: Face Reality | Page 51

Reality involves many players.

As you go through the mess, you’ll encounter several types of players:

- Current users: People who interact with whatever you’re making.

- Potential users: People you hope to reach.

- Stakeholders: People who care about the outcome of what you’re making.

- Competitors: People who share your current or potential users.

- Distractors: People that could take attention away from your intent.

You may play several of these roles yourself. Be aware of potential conflicts there.

For example, if you believe your users are like you but they’re not, there’s more room for incorrect assumptions and miscommunications.

Chapter 3: Face Reality | Page 71

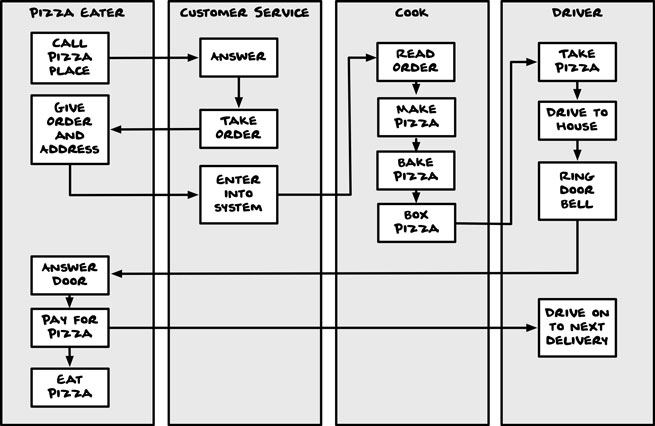

6. Swim Lane Diagram

A swim lane diagram depicts how multiple players work together to complete a task or interact within a process. The result is a list of tasks for each user. This is especially useful when you’re trying to understand how different teams or people work together.

Chapter 4: Choose a Direction | Page 100

Watch out for options and opinions.

When we talk about what something has to do, we sometimes answer with options of what it could do or opinions of what it should do.

A strong requirement describes the results you want without outlining how to get there.

A weak requirement might be written as: “A user is able to easily publish an article with one click of a button.” This simple sentence implies the interaction (one click), the interface (a button), and introduces an ambiguous measurement of quality (easily).

When we introduce implications and ambiguity into the process, we can unknowingly lock ourselves into decisions we don’t mean to make.

As an example, I once had a client ask for a “homepage made of buttons, not just text.” He had no idea that, to a web designer, a button is the way a user submits a form online. To my client, the word button meant he could change the content over time as his business changes.

Chapter 6: Play with Structure | Page 135

The way you organize things says a lot about you.

Classifying a tomato as a vegetable says something about what you know about your customers and your grocery store. You would classify things differently if you were working on a textbook for horticulture students, right?

How you choose to classify and organize things reflects your intent, but it can also reflect your worldview, culture, experience, or privilege.

Those same choices affect how people using your taxonomy understand what you share with them.

Taxonomies serve as a set of instructions for people interacting with our work.

Taxonomy is one of the strongest tools of rhetoric we have. The key to strong rhetoric is using language, rules and structures that your audience can easily understand and use.

Chapter 6: Play with Structure | Page 142

Most things need a mix of taxonomic approaches.

The world is organized in seemingly endless ways, but in reality, every form can be broken down into some taxonomic patterns.

Hierarchy, heterarchy, sequence, and hypertext are just a few common patterns. Most forms involve more than one of these.

A typical website has a hierarchical navigation system, a sequence for signing up or interacting with content, and hypertext links to related content.

A typical grocery store has a hierarchical aisle system, a heterarchical database for the clerk to retrieve product information by scanning a barcode, and sequences for checking out and other basic customer service tasks. I was even in a grocery store recently where each cart had a list of the aisle locations of the 25 most common products. A great use of hypertext.

A typical book has a sequence-based narrative, a hierarchical table of contents, and a set of facets allowing it to be retrieved with either the Dewey Decimal system at a library, or within a genre-based hierarchical system used in bookstores and websites like Amazon.com.