Mess (noun.)

Definition: A situation where the interactions between people and information are confusing or full of difficulties.

Also referenced as: Messes (noun) Messiness (noun) Messed (verb) Messy (adjective) Nonsensical (adjective) Chaos (noun)

Related to: Content, Data, Ecosystem, Information, Intent, Language, Mental Model, Object, Purpose, System, Understand

Chapter 1: Identify the Mess | Page 11

Messes are made of information and people.

A mess is any situation where something is confusing or full of difficulty. We all encounter messes.

Here are some of the many messes we deal with in our everyday lives:

- The structure of teams and organizations

- The processes we undertake in working together

- The ways products and services are represented, sold, and delivered to us

- The ways we communicate with each other

Chapter 1: Identify the Mess | Page 12

It’s hard to shine a light on the messes we face.

It’s hard to be the one to say that something is a mess. Like a little kid standing at the edge of a dark room, we can be paralyzed by fear and not even know how to approach the mess.

These are the moments where confusion, procrastination, self-criticism, and frustration keep us from changing the world.

The first step to taming any mess is to shine a light on it so you can outline its edges and depths.

Once you brighten up your workspace, you can guide yourself through the complex journey of making sense of the mess.

I wrote this simple guidebook to help even the least experienced sensemakers tame the messes made of information (and people!) they’re sure to encounter.

Chapter 1: Identify the Mess | Page 16

People architect information.

It’s easy to think about information messes as if they’re an alien attack from afar. But they’re not.

We made these messes.

When we architect information, we determine the structures we need to communicate our message.

Everything around you was architected by another person. Whether or not they were aware of what they were doing. Whether or not they did a good job. Whether or not they delegated the task to a computer.

Information is a responsibility we all share.

We’re no longer on the shore watching the information age approach; we’re up to our hips in it.

If we’re going to be successful in this new world, we need to see information as a workable material and learn to architect it in a way that gets us to our goals.

Chapter 1: Identify the Mess | Page 17

Every thing is complex.

Some things are simple. Some things are complicated. Every single thing in the universe is complex.

Complexity is part of the equation. We don’t get to choose our way out of it.

Here are three complexities you may encounter:

- A common complexity is lacking a clear direction or agreeing on how to approach something you are working on with others.

- It can be complex to create, change, access, and maintain useful connections between people and systems, but these connections make it possible for us to communicate.

- People perceive what’s going on around them in different ways. Differing interpretations can make a mess complex to work through.

Chapter 1: Identify the Mess | Page 18

Knowledge is complex.

Knowledge is surprisingly subjective.

We knew the earth was flat, until we knew it was not flat. We knew that Pluto was a planet until we knew it was not a planet.

True means without variation, but finding something that doesn’t vary feels impossible.

Instead, to establish the truth, we need to confront messes without the fear of unearthing inconsistencies, questions, and opportunities for improvement. We need to be open to the variations of truth that are bound to exist.

Part of that includes agreeing on what things mean. That’s our subjective truth. And it takes courage to unravel our conflicts and assumptions to determine what’s actually true.

If other people have a different interpretation of what we’re making, the mess can seem even bigger and more hairy. When this happens, we have to proceed with questions and set aside what we think we know.

Chapter 1: Identify the Mess | Page 19

Every thing has information.

Over your lifetime, you’ll make, use, maintain, consume, deliver, retrieve, receive, give, consider, develop, learn, and forget many things.

This book is a thing. Whatever you’re sitting on while reading is a thing. That thing you were thinking about a second ago? That’s a thing too.

Things come in all sorts, shapes, and sizes.

The things you’re making sense of may be analog or digital; used once or for a lifetime; made by hand or manufactured by machines.

I could have written a book about information architecture for websites or mobile applications or whatever else is trendy. Instead, I decided to focus on ways people could wrangle any mess, regardless of what it’s made of.

That’s because I believe every mess and every thing shares one important non-thing:information.

Information is whatever is conveyed or represented by a particular arrangement or sequence of things.

Chapter 1: Identify the Mess | Page 25

Stakeholders are complex.

A stakeholder is someone who has a viable and legitimate interest in the work you’re doing. Our stakeholders can be partners in business, life, or both.

Managers, clients, coworkers, spouses, family members, and peers are common stakeholders.

Sometimes we choose our stakeholders; other times, we don’t have that luxury. Either way, understanding our stakeholders is crucial to our success. When we work against each other, progress comes to a halt.

Working together is difficult when stakeholders see the world differently than we do.

But we should expect opinions and personal preferences to affect our progress. It’s only human to consider options and alternatives when we’re faced with decisions.

Most of the time, there is no right or wrong way to make sense of a mess. Instead, there are many ways to choose from. Sometimes we have to be the one without opinions and preferences so we can weigh all the options and find the best way forward for everyone involved.

Chapter 1: Identify the Mess | Page 26

To do is to know.

Knowing is not enough. Knowing too much can encourage us to procrastinate. There’s a certain point when continuing to know at the expense of doing allows the mess to grow further.

Practicing information architecture means exhibiting the courage to push past the edges of your current reality. It means asking questions that inspire change. It takes honesty and confidence in other people.

Sometimes, we have to move forward knowing that other people tried to make sense of this mess and failed. We may need to shine the light brighter or longer than they did. Perhaps now is a better time. We may know the outcomes of their fate, but we don’t know our own yet. We can’t until we try.

What if turning on the light reveals that the room is full of scary trolls? What if the light reveals the room is actually empty? Worse yet, what if turning on the light makes us realize we’ve been living in darkness?

The truth is that these are all potential realities, and understanding that is part of the journey. The only way to know what happens next is to do it.

Chapter 1: Identify the Mess | Page 27

Meet Carl.

Carl is a design student getting ready to graduate. But first, he has to produce a book explaining his design work and deliver a ten-minute presentation.

While Carl is a talented designer, public speaking makes him queasy and he doesn’t consider himself much of a writer. He has drawers and boxes full of notes, scribbles, sketches, magazine clippings, quotes, and prototypes.

Carl has the pieces he needs to make his book and presentation come to life. He also has a momentum-killing fear of the mess he’s facing.

To help Carl identify his mess, we could start by asking questions about its edges and depths:

- Who are his users and what does he know about them already? How could he find out more?

- Who are the stakeholders and what does he know about what they are expecting?

- How does he want people to interpret the work? What content would help that interpretation?

- What might distract from that interpretation?

Chapter 1: Identify the Mess | Page 28

It’s your turn.

This chapter outlines why it’s important to identify the edges and depths of a mess, so you can lessen your anxiety and make progress.

I also introduced the need to look further than what is true, and pay attention to how users and stakeholders interpretlanguage, data, and content.

To start to identify the mess you’re facing, work through these questions:

- Users: Who are your intended users? What do you know about them? How can you get to know them better? How might they describe this mess?

- Stakeholders: Who are your stakeholders? What are their expectations? What are their thoughts about this mess? How might they describe it?

- Information: What interpretations are you dealing with? What information is being created through a lack of data or content?

- Current state: Are you dealing with too much information, not enough information, not the right information, or a combination of these?

Chapter 2: State your Intent | Page 35

Looking good versus being good.

Pretty things can be useless, and ugly things can be useful. Beauty and quality are not always related.

When making things, we should aim to give equal attention to looking good and being good. If either side of that duality fails, the whole suffers.

As users, we may assume that a good-looking thing will also be useful and well thought-out. But it only takes a minute or two to see if our assumptions are correct. If it isn’t good, we’ll know.

As sensemakers, we may fall victim to these same assumptions about the relationships between beauty and quality of thought.

Beware of pretty things. Pretty things can lie and hide from reality. Ugly things can too.

If we’re going to sort out the messes around us, we need to ask difficult questions and go deeper than how something looks to determine if it’s good or not.

Chapter 2: State your Intent | Page 37

Meaning can get lost in translation.

Did you ever play the telephone game as a child?

It consists of a group of kids passing a phrase down the line in a whisper. The point of the game is to see how messed up the meaning of the initial message becomes when sent across a messy human network.

Meaning can get lost in subtle ways. It’s wrapped up in perception, so it’s also subjective. Most misunderstandings stem from mixed up meanings and miscommunication of messages.

Miscommunications can lead to disagreements and frustration, especially when working with others.

Getting our message across is something everyone struggles with. To avoid confusing each other, we have to consider how our message could be interpreted.

Chapter 3: Face Reality | Page 50

By facing reality, we can find solutions.

Whenever we’re making something, there are moments when it’s no longer time to ponder. It’s time to act, to make, to realize, and perhaps to fail.

Fear is an obvious but elusive partner in these moments. Fear can walk ahead of us and get all the glory, leaving us pondering and restless for more, more, more. Maybe we fear failure. Maybe we fear success. Maybe we fear light being shined our way.

Confronting your fears and knowing what is real is an important part of making sense of a mess.

Facing reality is the next step on our journey. In this chapter, we’ll discuss rabbit holes of reality you are likely to have to explore as well as some diagrammatic techniques you can take with you to document what you find down there.

Before we go on, I have to warn you of the many opportunities ahead to lose faith in yourself as you climb through and understand the details of your reality. It can start to feel like the mess wants you to fail in making sense of it. Don’t worry. That thought has occurred to everyone who has ever tried to change something. We all have to deal with reality. We all want what we want and then get what we get.

Chapter 3: Face Reality | Page 51

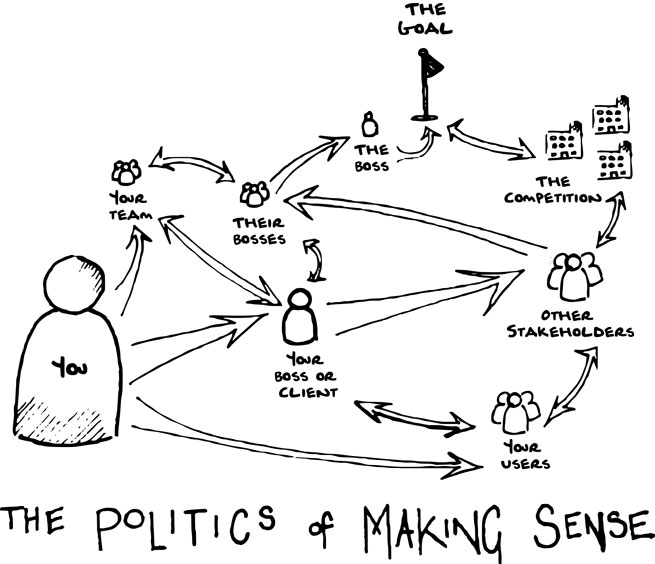

Reality involves many players.

As you go through the mess, you’ll encounter several types of players:

- Current users: People who interact with whatever you’re making.

- Potential users: People you hope to reach.

- Stakeholders: People who care about the outcome of what you’re making.

- Competitors: People who share your current or potential users.

- Distractors: People that could take attention away from your intent.

You may play several of these roles yourself. Be aware of potential conflicts there.

For example, if you believe your users are like you but they’re not, there’s more room for incorrect assumptions and miscommunications.

Chapter 3: Face Reality | Page 54

Reality has many intersections.

Tweeting while watching TV is an example of two channels working together to support a single context.

A single channel can also support multiple contexts.

For example, a website may serve someone browsing on a phone from their couch, on a tablet at a coffee shop, or on a desktop computer in a cubicle.

When you begin to unravel a mess, it’s easy to be overwhelmed by the amount of things that need to come together to support even the simplest of contexts gracefully on a single channel.

“It’s just a ____________” is an easy trap to fall into. But to make sense of real-world problems, you need to understand how users, channels, and context relate to each other.

What channels do your users prefer? What context are they likely in when encountering what you’re making? How are they feeling? Are they in a hurry? Are they on slow Wi-Fi? Are they there for entertainment or to accomplish a task?

Considering these small details will make a huge difference for you and your users.

Chapter 3: Face Reality | Page 64

Keep it tidy.

If people judge books by their covers, they judge diagrams by their tidiness.

People use aesthetic cues to determine how legitimate, trustworthy, and useful information is. Your job is to produce a tidy representation of what you’re trying to convey without designing it too much or polishing it too early in the process.

As you make your diagram, keep your stakeholders in mind. Will they understand it? Will anything distract them? Crooked lines, misspellings, and styling mistakes lead people astray. Be careful not to add another layer of confusion to the mess.

Make it easy to make changes so you can take in feedback quickly and keep the conversation going, rather than defending or explaining the diagram.

Your diagram ultimately needs to be tidy enough for stakeholders to understand and comment on it, while being flexible enough to update.

Chapter 3: Face Reality | Page 65

Expand your toolbox.

Objects like diagrams, maps, and charts aren’t one-size-fits-all. Play with them, adapt them, and expand on them for your own purposes.

The biggest mistake I see beginner sensemakers make is not expanding their toolbox of diagrammatic and mapping techniques.

There are thousands, maybe millions, of variations on the form, quality, and testing of diagrams and maps. And more are being created and experimented with each day.

The more diagrams you get to know, the more tools you have. The more ways you can frame the mess, the more likely you are to see the way through to the other side.

To help you build your toolbox, I’ve included ten diagrams and maps I use regularly in my own work.

As you review each one, imagine the parts of your mess that could benefit from reframing.

Chapter 3: Face Reality | Page 78

Face your reality.

Everything is easier with a map. Let me guide you through making a map for your own mess.

On the following page is another favorite diagram of mine, the matrix diagram.

The power of a matrix diagram is that you can make the boxes collect whatever you want. Each box becomes a task to fulfill or a question to answer, whether you’re alone or in a group.

Matrix diagrams are especially useful when you’re facilitating a discussion, because they’re easy to create and they keep themselves on track. An empty box means you’re not done yet.

After making a simple matrix of users, contexts, players, and channels, you’ll have a guide to understanding the mess. By admitting your hopes and fears, you’re uncovering the limits you’re working within.

This matrix should also help you understand the other diagrams and objects you need to make, along with who will use and benefit from them.

Chapter 4: Choose a Direction | Page 104

Control your vocabulary.

Are you facing a mess like Rasheed’s? Do your stakeholders speak the same language? Do you collectively speak the same language as your users? What language might be troublesome in the context of what you are doing? What concepts need to be better understood or defined?

To control your vocabulary:

- Create a list of terms to explore.

- Define each term as simply as you can.

- Underline words within your definitions that need to be further defined, and define them.

- Document the history, alternatives, and myths associated with each term.

- Review your list of defined terms with some of your users. Refine the list based on their feedback.

- Create a list of requirements that join your nouns and verbs together.

Chapter 4: Choose a Direction | Page 87

There are spaces between the places we make.

When you’re cleaning up a big mess, assess the spaces between places as well as the places themselves.

A place is a space designated for a specific purpose.

For example, if you built a public park, you might make a path to walk on, a picnic area, a playground, some bathrooms, and a soccer field. These areas were made with tasks in mind.

If parkgoers wear down a path through your fresh laid grass, you as the parkitect (ha!) could see it as an annoyance. Or you could see it as a space between places and pave over it so people can get where they want to go without walking through the mud.

A space is an open, free, or unoccupied area.

Space may not have a designated purpose yet, but that doesn’t stop users from going there.

No matter what you’re making, your users will find spaces between places. They bring their own context and channels with them, and they show you where you should go next. Find areas in flux and shine a light on them.

Chapter 4: Choose a Direction | Page 91

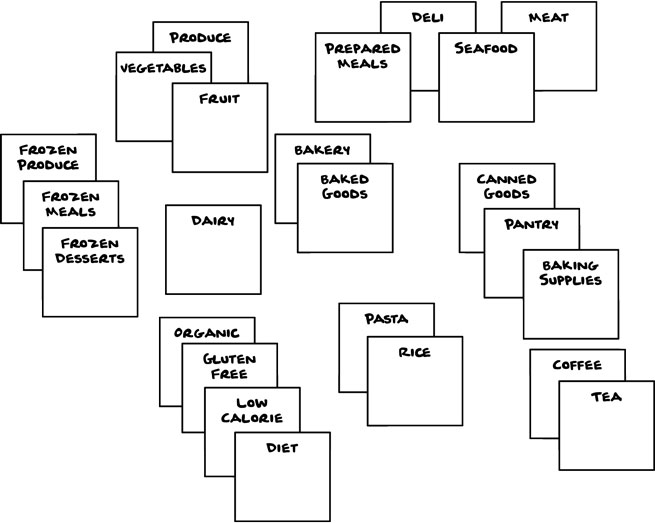

Your ontology already exists.

Ontology always exists, but the one you have today may be messy or nonsensical. If you were trying to understand the ontology of your grocery store, your map might look like this at first:

By asking your customers for words they think about within a grocery store, your map could grow to reflect overlapping and related terms.

If you were choosing words for the aisle and department signs or the website, this exercise would help you along.

Chapter 4: Choose a Direction | Page 98

Think about nouns and verbs.

Nouns represent each of the objects, people, and places involved in a mess.

As an example, a post is a noun commonly associated with another noun, an author.

Verbs represent the actions that can be taken.

A post (n.) can be: written, shared, deleted, or read.

Verbs don’t exist without nouns. For example, an online share button implies that it will share this post.

Nouns are often created as a result of verbs. A post only exists after posting

It’s easy to adopt terms that are already in use or to be lazy in choosing our language. But when you’re deciding which words to use, it is important to consider the alternatives, perceptions, and associations around each term.

How would your work be different if “authors writing posts” was changed to “researchers authoring papers,” or “followers submitting comments?”

Chapter 6: Play with Structure | Page 131

Ambiguity hides in simplicity.

Imagine that on your first day working at a record store, your manager says, “Our records are organized alphabetically.” Under this direction, you file your first batch of vinyl with ease.

Later, you overhear a coworker saying, “Sorry, it looks like we’re sold out of Michael Jackson right now.”

Your manager looks under “J” and checks the inventory, which says the store should have a single copy of Thriller.

You remember that it was part of the shipment of records you just filed. Where else could you have put that record, if not under “J”? Maybe under “M”?

The ambiguity that’s wrapped up in something as simple as “alphabetize these” is truly amazing.

We give and receive instructions all day long. Ambiguous instructions can weaken our structures and their trustworthiness. It’s only so long after that first album is misfiled that chaos ensues.

Chapter 6: Play with Structure | Page 144

Play with Structure

Because your structure may change a hundred times before you finish making it, you can save time and frustration by thinking with boxes and arrows before making real changes. Boxes and arrows are easier to move around than the other materials we work with, so start there.

Try structuring the mess with common patterns of boxes and arrows as shown on the next page. Remember that you’ll probably need to combine more than one pattern to find a structure that works.

- Assess the content and facets that are useful for what you’re trying to convey.

- Play with broad and shallow versus narrow and deep hierarchies. Consider the right place to use heterarchies, sequences, and hypertext arrangements.

- Arrange things one way and then come up with another way. Compare and contrast them. Ask other people for input.

- Think about the appropriate level of ambiguity or exactitude for classifying and labeling things within the structure you’re pursuing.

Chapter 7: Prepare to Adjust | Page 148

Adjustments are a part of reality.

From moment to moment, the directions we choose forever change the objects we make, the effects we see, and the experiences we have.

As we move towards our goals, things change and new insights become available. Things always change when we begin to understand what we couldn’t make sense of before. As a sensemaker, the most important skill you can learn is to adjust your course to accommodate new forces as you encounter them on your journey.

Don’t seek finalization. Trying to make something that will never change can be super frustrating. Sure, it’s work to move those boxes and arrows around as things change. But that is the work, not a reason to avoid making a plan. Taking in feedback from other people and continuously refining the pieces as well as the whole is what assures that something is “good.”

Don’t procrastinate. Messes only grow with time. You can easily make excuses and hold off on doing something until the conditions are right, or things seem stable.

Perfection isn’t possible, but progress is.

Chapter 7: Prepare to Adjust | Page 151

Argue about discuss it until it’s clear.

It’s totally normal for fear, anxiety, and linguistic insecurity to get in the way of progress. Learning to work with others while they’re experiencing these not-so-pleasant realities is the hardest part of making sense of a mess.

Tension can lead to arguments. Arguments can cause resentment. Resentment can kill momentum. And when momentum stalls, messes grow larger and meaner.

To get through the tension, try to understand other people’s positions and perceptions:

Chapter 7: Prepare to Adjust | Page 153

We serve many masters.

No matter what the mess is made of, we have many masters, versions of reality, and needs to serve. Information is full of history and preconceptions.

Stakeholders need to:

- Know where the project is headed

- See patterns and potential outcomes

- Frame the appropriate solution for users

Users need to:

- Know how to get around

- Have a sense of what’s possible based on their needs and expectations

- Understand the intended meaning

It’s our job to uncover subjective reality.

An important part of that is identifying the differences between what stakeholders think users need and what users think they need for themselves.

Chapter 7: Prepare to Adjust | Page 156

Be the filter, not the grounds.

When making a cup of coffee, the filter’s job is to get the grit out before a user drinks the coffee. Sensemaking is like removing the grit from the ideas we’re trying to give to users.

What we remove is as important as what we add. It isn’t just the ideas that get the work done.

Be the one not bringing the ideas. Instead, be the filter that other people’s ideas go through to become drinkable:

- Shed light on the messes that people see but don’t talk about.

- Make sure everyone agrees on the intent behind the work you’re doing together.

- Help people choose a direction and define goals to track your progress.

- Evaluate and refine the language and structures you use to pursue those goals.

With those skills, you’ll always have people who want to work with you.

Chapter 7: Prepare to Adjust | Page 158

It’s far more rewarding than hard.

It’s rewarding to set a goal and reach it.

It’s rewarding to know that you’re communicating in a language that makes sense to others.

It’s rewarding to help someone understand something in a way they hadn’t before.

It’s rewarding to see positive changes from the insights you gather.

It’s rewarding to know that something is good.

It’s rewarding to give the gifts of clarity, realistic expectations, and clear direction.

It’s rewarding to make this world a little clearer.

It’s rewarding to make sense of the messes you face.

Chapter 7: Prepare to Adjust | Page 159

Meet Abby.

Abby Covert is an information architect. After ten years of practicing information architecture for clients, Abby worried that too few people knew how to practice it themselves. She decided that the best way to help would be to teach this important practice.

After two years of teaching without a textbook, Abby told her students that she intended to write the book that was missing from the world: a book about information architecture for everybody.

As she wrote the first draft, she identified a mess of inconsistencies in the language and concepts inherent in teaching an emerging practice. At the end of the semester, she had a textbook for art school students, but she didn’t have the book that she intended to write for everybody. She had gone in the wrong direction to achieve a short-term goal.

She was frustrated and fearful of starting over. But instead of giving up, Abby faced her reality and used the advice in this book to make sense of her mess.

To get to the book you are reading, she wrote over 75,000 words, defined over 100 terms as simply as she could, and tested three unique prototypes with her users.

She hopes that it makes sense.

Chapter 7: Prepare to Adjust | Page 160

Make sense yet?

- Have you explored the depth and edges of the mess that you face?

- Do you know why you have the intent you have and what it means to how you will solve your problem?

- Have you faced reality and thought about contexts and channels your users could be in?

- What language have you chosen to use to clarify your direction?

- What specific goals and baselines will you measure your progress against?

- Have you put together various structures and tested them to make sure your intended message comes through to users?

- Are you prepared to adjust?