Communication (noun.)

Definition: The act of transmitting thoughts, messages, or information to people or systems.

Also referenced as: Communicate (verb) Communicated (verb) Communcating (verb)

Related to: Channel, Content, Data, Design, Frame, Information, Intent, Language, Purpose

Chapter 1: Identify the Mess | Page 11

Messes are made of information and people.

A mess is any situation where something is confusing or full of difficulty. We all encounter messes.

Here are some of the many messes we deal with in our everyday lives:

- The structure of teams and organizations

- The processes we undertake in working together

- The ways products and services are represented, sold, and delivered to us

- The ways we communicate with each other

Chapter 1: Identify the Mess | Page 16

People architect information.

It’s easy to think about information messes as if they’re an alien attack from afar. But they’re not.

We made these messes.

When we architect information, we determine the structures we need to communicate our message.

Everything around you was architected by another person. Whether or not they were aware of what they were doing. Whether or not they did a good job. Whether or not they delegated the task to a computer.

Information is a responsibility we all share.

We’re no longer on the shore watching the information age approach; we’re up to our hips in it.

If we’re going to be successful in this new world, we need to see information as a workable material and learn to architect it in a way that gets us to our goals.

Chapter 1: Identify the Mess | Page 17

Every thing is complex.

Some things are simple. Some things are complicated. Every single thing in the universe is complex.

Complexity is part of the equation. We don’t get to choose our way out of it.

Here are three complexities you may encounter:

- A common complexity is lacking a clear direction or agreeing on how to approach something you are working on with others.

- It can be complex to create, change, access, and maintain useful connections between people and systems, but these connections make it possible for us to communicate.

- People perceive what’s going on around them in different ways. Differing interpretations can make a mess complex to work through.

Chapter 1: Identify the Mess | Page 20

What’s information?

Information is not a fad. It wasn’t even invented in the information age. As a concept, information is old as language and collaboration is.

The most important thing I can teach you about information is that it isn’t a thing. It’s subjective, not objective. It’s whatever a user interprets from the arrangement or sequence of things they encounter.

For example, imagine you’re looking into a bakery case. There’s one plate overflowing with oatmeal raisin cookies and another plate with a single double-chocolate chip cookie. Would you bet me a cookie that there used to be more double-chocolate chip cookies on that plate? Most people would take me up on this bet. Why? Because everything they already know tells them that there were probably more cookies on that plate.

The belief or non-belief that there were other cookies on that plate is the information each viewer interprets from the way the cookies were arranged. When we rearrange the cookies with the intent to change how people interpret them, we’re architecting information.

While we can arrange things with the intent to communicate certain information, we can’t actually make information. Our users do that for us.

Chapter 2: State your Intent | Page 33

What is good?

Language is any system of communication that exists to establish shared meaning. Even within a single language, one term can mean something in situation A and something different in situation B. We call this a homograph. For example, the word pool can mean a swimming pool, shooting pool, or a betting pool.

Perception is the process of considering, and interpreting something. Perception is subjective like truth is. Something that’s beautiful to one person may be an eyesore to another. For example, many designers would describe the busy, colorful patterns in the carpets of Las Vegas as gaudy. People who frequent casinos often describe them as beautiful.

However good or bad these carpet choices seem to us, there are reasons why they look that way. Las Vegas carpets are busy and colorful to disguise spills and wear and tear from foot traffic. Gamblers likely enjoy how they look because of an association with an activity that they enjoy. For Las Vegas casino owners and their customers, those carpet designs are good. For designers, they’re bad. Neither side is right. Both sides have an opinion.

What we intend to do determines how we define words like good and bad.

Chapter 2: State your Intent | Page 38

Who matters?

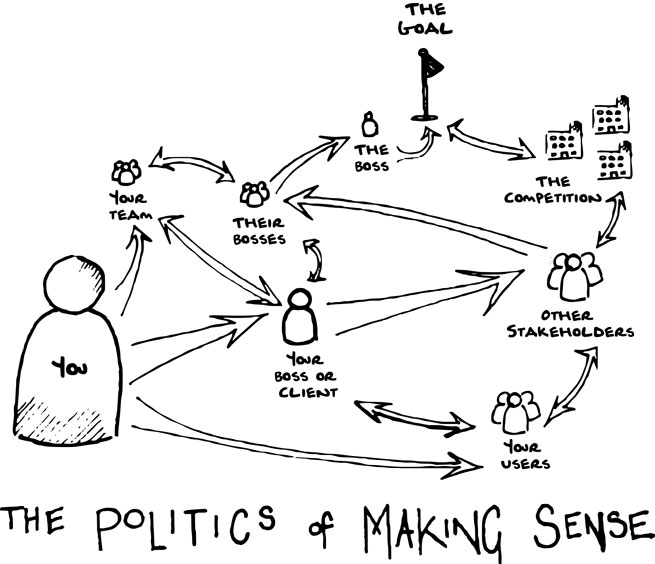

The meaning we intend to communicate doesn’t matter if it makes no sense, or the wrong sense, to the people we want to reach.

We need to consider our intended users. Sometimes they’re our customers or the public. Often times, they’re also stakeholders, colleagues, employees, partners, superiors, or clients. These are the people who use our process.

To determine who matters, ask these questions:

Chapter 2: State your Intent | Page 41

How varies widely.

The saying “there are many ways to skin a cat” reminds us that we have options when it comes to achieving our intent. There are many ways to do just about anything

Whether you’re working on a museum exhibit, a news article, or a grocery store, you should explore all of your options before choosing a direction.

How is an ever-growing list of directions we could take while staying true to our reasons why.

To look at your options, ask yourself:

Chapter 2: State your Intent | Page 45

Meet Karen.

Karen is a product manager at a startup. Her CEO thinks the key to launching their product in a crowded market is a sleek look and feel.

Karen recently conducted research to test the product with its intended users. With the results in hand, she worries that what the CEO sees as sleek is likely to seem cold to the users they want to reach.

Karen has research on her side, but she still needs to define what good means for her organization. Her team needs to state their intent.

To establish an intent, Karen talks with her CEO about how their users’ aesthetic wants don’t line up with the look and feel of the current product.

She starts their conversation by confirming that the users from her research are part of the intended audience for the product.

Next, she helps the CEO create a list of questions and actions the research brought up.

Afterwards, Karen develops a plan for communicating her findings to the rest of the team.

Chapter 3: Face Reality | Page 61

Rhetoric matters.

Rhetoric is communication designed to have a persuasive effect on its audience.

Here are some common rhetorical reasons for making diagrams and maps:

- Reflection: Point to a future problem (e.g., a map of a local landfill’s size in the past, present, and projected future).

- Options: Show something as it could be (e.g., a diagram showing paths a user could take to set up an application).

- Improvements: Show something as it should be (e.g., a diagram pointing out opportunities found during user research).

- Identification: Show something as it once was or is today (e.g., a map of your neighborhood).

- Plan: Show something as it will be (e.g., a map of your neighborhood with bike lanes).

Chapter 4: Choose a Direction | Page 102

Admit where you are.

Let’s say you’re on a weeklong bicycle trip. You planned to make it to your next stop before dark, but a flat tire delayed you by a few hours.

Even though you planned to get further along today, the truth is that pursuing that plan would be dangerous now.

Similarly, an idea you can draw on paper in one day may end up taking you a lifetime to make real. With the ability to make plans comes great responsibility.

Think about what you can do with the time and resources you have. Filtering and being realistic are part of the job. Keep reevaluating where you are in relation to where you want to go.

Be careful not to fall in love with your plans or ideas. Instead, fall in love with the effects you can have when you communicate clearly.

Chapter 4: Choose a Direction | Page 88

Language matters.

I once had a project where the word “asset” was defined three different ways across five teams.

I once spent three days defining the word “customer”.

I once defined and documented over a hundred acronyms in the first week of a project for a large company, only to find 30 more the next week.

I wish I could say that I’m exaggerating or that any of this effort was unnecessary. Nope. Needed.

Language is complex. But language is also fundamental to understanding the direction we choose. Language is how we tell other people what we want, what we expect of them, and what we hope to accomplish together.

Without language, we can’t collaborate.

Unfortunately, it’s far too easy to declare a direction in language that doesn’t make sense to those it needs to support: users, stakeholders, or both.

When we don’t share a language with our users and our stakeholders, we have to work that much harder to communicate clearly.

Chapter 6: Play with Structure | Page 130

Ambiguity costs clarity; exactitude costs flexibility.

The more ambiguous you are, the more likely it is that people will have trouble using your taxonomy to find and classify things.

For every ambiguous rule of classification you use or label you hide behind, you’ll have to communicate your intent that much more clearly.

For example, what if I had organized the lexicon in the back of this book by chapter, instead of alphabetically? This might be an interesting way of arranging things, but it would need to be explained, so you could find a term.

The more exact your taxonomy becomes, the less flexible it is. This isn’t always bad, but it can be. If you introduce something that doesn’t fit into a category things can get confusing.

Because there are many words for the same thing, exact classifications can slow us down. For example, I recently tried to buy some zucchini at a grocery store. But it wasn’t until the clerk in training found the code for “Squash, Green” that she could ring me up.