Experience (noun.)

Definition: An event or occurrence that leaves an impression on someone.

Also referenced as: Experiencing (verb) Experienced (adjective) Experiences (noun)

Related to: Complex, Ecosystem, Interact, Interface, Journey, Prototype, Schematic, Sense Making, Sequence, System, User

Chapter 1: Identify the Mess | Page 12

It’s hard to shine a light on the messes we face.

It’s hard to be the one to say that something is a mess. Like a little kid standing at the edge of a dark room, we can be paralyzed by fear and not even know how to approach the mess.

These are the moments where confusion, procrastination, self-criticism, and frustration keep us from changing the world.

The first step to taming any mess is to shine a light on it so you can outline its edges and depths.

Once you brighten up your workspace, you can guide yourself through the complex journey of making sense of the mess.

I wrote this simple guidebook to help even the least experienced sensemakers tame the messes made of information (and people!) they’re sure to encounter.

Chapter 1: Identify the Mess | Page 24

Users are complex.

User is another word for a person. But when we use that word to describe someone else, we’re likely implying that they’re using the thing we’re making. It could be a website, a product or service, a grocery store, a museum exhibit, or anything else people interact with.

When it comes to our use and interpretation of things, people are complex creatures.

We’re full of contradictions. We’re known to exhibit strange behaviors. From how we use mobile phones to how we traverse grocery stores, none of us are exactly the same. We don’t know why we do what we do. We don’t really know why we like what we like, but we do know it when we see it. We’re fickle.

We expect things to be digital, but also, in many cases, physical. We want things to feel auto-magic while retaining a human touch. We want to be safe, but not spied on. We use words at our whim.

Most importantly perhaps, we realize that for the first time ever, we have easy access to other people’s experiences to help us decide if something is worth experiencing at all.

Chapter 2: State your Intent | Page 40

What before how.

There are reasons it makes sense to wait to cook until after you know what you’re making. For these same reasons, we all know not to construct a building without a plan.

When we jump into a task without thinking about what we’re trying to accomplish, we can end up with solutions to the wrong problem. We can waste energy that would be better spent determining which direction to take.

When deciding what you’re doing, ask yourself:

- What are you trying to change? What is your vision for the future? What is within your abilities?

- What do you know about the quality of what exists today? What further research will help you understand it?

- What has been done before? What can you learn from those experiences? What is the market and competition like? Has anyone succeeded or failed at this in the past?

Chapter 3: Face Reality | Page 53

Reality happens across channels and contexts.

A channel transmits information. A commercial on TV and YouTube is accessible on two channels. A similar message could show up in your email inbox, on a billboard, on the radio, or in the mail.

We live our lives across channels.

It’s common to see someone using a smartphone while sitting in front of a computer screen, or reading a magazine while watching TV.

As users, our context is the situation we’re in, including where we are, what we’re trying to do, how we’re feeling, and anything else that shapes our experience. Our context is always unique to us and can’t be relied upon to hold steady.

If I’m tweeting about a TV show while watching it, my context is “sitting on my couch, excited enough about what I’m watching to share my reactions.”

In this context, I’m using several different channels: Twitter, a smartphone, and TV.

Chapter 3: Face Reality | Page 55

Reality doesn’t always fit existing patterns.

Beware of jumping into an existing solution or copying existing patterns. In my experience, too many people buy into an existing solution’s flexibility to later discover its rigidity.

Imagine trying to design a luxury fashion magazine using a technical system for grocery store coupons. The features you need may seem similar enough until you consider your context. That’s when reality sets in.

What brings whopping returns to one business might crush another. What works for kids might annoy older people. What worked five years ago may not work today.

We have to think about the effects of adopting an existing structure or language before doing so.

When architecting information, focus on your own unique objectives. You can learn from and borrow from other people. But it’s best to look at their decisions through the lens of your intended outcome.

Chapter 3: Face Reality | Page 57

Objects let us have deeper conversations about reality.

When you discuss a specific subject, you subconsciously reference part of a large internal map of what you know.

Other people can’t see this map. It only exists in your head, and it’s called your mental model.

When faced with a problem, you reference your mental model and try to organize the aspects and complexities of what you see into recognizable patterns. Your ongoing experience changes your mental model. This book is changing it right now.

We create objects like maps, diagrams, prototypes, and lists to share what we understand and perceive. Objects allow us to compare our mental models with each other.

These objects represent our ideas, actions, and insights. When we reference objects during a conversation, we can go deeper and be more specific than verbalizing alone.

As an example, it’s much easier to teach someone about the inner-workings of a car engine with a picture, animation, diagram, or working model.

Chapter 3: Face Reality | Page 75

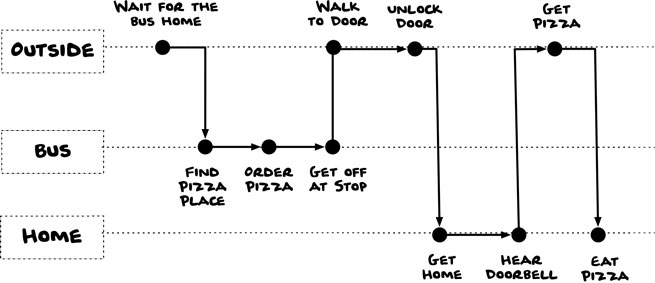

10. Journey Map

A journey map shows all of the steps and places that make up a person or group’s experience.

The rows represent the user’s context (e.g., outside, on the bus, at home). Each point represents an event or a task that makes up the overall journey. Each point is placed sequentially as it relates to the other points.

This example shows events that only involve one person, but journey maps are also useful for showing the movement of pairs, teams, and organizations.

Chapter 4: Choose a Direction | Page 85

These levels deeply affect one another.

Once you know what level you’re working at, you can zoom in to the appropriate level of detail. Sometimes we need to zoom all the way in on an object. Other times it’s more important to zoom out to look at the ecosystem. Being able to zoom in and out as you work is the key to seeing how these levels affect one another.

When you’re deep in the details, it’s easy to forget your broad effect. When you’re working overhead, it’s easy to forget how your decisions affect things down on the ground. Making changes at one level without considering the affects they have on other levels can lead to friction and dissatisfaction between our users, our stakeholders, and us. One tiny change can spark a thousand disruptions.

For example, if we owned a restaurant and decided to eliminate paper napkins to be environmentally friendly, that would impact the entire restaurant, not just the table service our diners experience.

We’d need to consider other factors like where dirty napkins go, how we collect them, how often they’re picked up and cleaned, how many napkins we need on hand between cleanings, and if we should use paper napkins if something spills in the dining room.

One tiny decision leads to another, and another.

Chapter 4: Choose a Direction | Page 89

Reduce linguistic insecurity.

The average person gives and receives directions all day long, constantly experiencing the impact of language and context. Whether it’s a grocery list from a partner or a memo from a manager, we’ve all experienced what happens when a poor choice of words leads to the wrong outcome. Whether we’re confused by one word or the entire message, the anxiety that comes from misunderstanding someone else’s language is incredibly frustrating.

Imagine that on your first day at a new job every concept, process, and term you’re taught is labeled with nonsense jargon. Now imagine the same first day, only everything you’re shown has clear labels you can easily remember. Which second day would you want?

We can be insecure or secure about the language we’re expected to use. We all prefer security.

Linguistic insecurity is the all too common fear that our language won’t conform to the standard or style of our context.

To work together, we need to use language that makes sense to everyone involved.

Chapter 4: Choose a Direction | Page 94

Create a list of words you don’t say.

A controlled vocabulary doesn’t have to end with terms you intend to use. Go deeper by defining terms and concepts that misalign with your intent.

For the sake of clarity, you can also define:

- Terms and concepts that conflict with a user’s mental model of how things work

- Terms and concepts that have alternative meaning for users or stakeholders

- Terms and concepts that carry historical, political, or cultural baggage

- Acronyms and homographs that may confuse users or stakeholders

In my experience, a list of things you don’t say can be even more powerful than a list of things you do. I’ve been known to wear a whistle and blow it in meetings when someone uses a term from the don’t list.

Chapter 4: Choose a Direction | Page 95

Words I don’t say in this eBook.

I’ve avoided using these terms and concepts:

- Doing/Do the IA (commonly misstated)

- IA (as an abbreviation)

- Information Architecture (as a proper noun)

- Information Architect (exceptions in my dedication and bio pages)

- App as an abbreviation (too trendy)

- Very (the laziest word ever)

- User experience (too specific to design)

- Metadata (too technical)

- Semantic (too academic)

- Semiotic (too academic)

I have reasons why these words aren’t good in the context of this book. That doesn’t mean I never use them; I do in some contexts.

Chapter 5: Measure the Distance | Page 118

Fuzzy is normal.

What is good for one person can be profoundly bad for another, even if their goal is roughly the same. We each live within a unique set of contradictions and experiences that shape how we see the world.

Remember that there’s no right or wrong way to do something. Words like right and wrong are subjective.

The important part is being honest about what you intend to accomplish within the complicated reality of your life. Your intent may differ from other people; you may perceive things differently.

You may be dealing with an indicator that’s surprisingly difficult to measure, a data source that’s grossly unreliable, or a perceptual baseline that’s impossible to back up with data.

But as fuzzy as your lens can seem, setting goals with incomplete data is still a good way to determine if you’re moving in the right direction.

Uncertainty comes up in almost every project. But you can only learn from those moments if you don’t give up. Stick with the tasks that help you clarify and measure the distance ahead.

Chapter 6: Play with Structure | Page 127

We combine taxonomies to create unique forms.

Taxonomies shape our experience at every level. We use taxonomies to make sense of everything from systems to objects. It often takes multiple taxonomic approaches to make sense of a single form.

A Form is the visual shape or configuration something takes. The form is what users actually experience.

Even a simple form like this book uses several taxonomies to help you read through the content, understand it, and use it.

A few taxonomies in this book:

- Table of contents

- Chapter sequence

- Page numbers

- Headlines that accompany brief expansions on an individual lesson

- An Indexed lexicon

- Links to worksheets

Chapter 6: Play with Structure | Page 135

The way you organize things says a lot about you.

Classifying a tomato as a vegetable says something about what you know about your customers and your grocery store. You would classify things differently if you were working on a textbook for horticulture students, right?

How you choose to classify and organize things reflects your intent, but it can also reflect your worldview, culture, experience, or privilege.

Those same choices affect how people using your taxonomy understand what you share with them.

Taxonomies serve as a set of instructions for people interacting with our work.

Taxonomy is one of the strongest tools of rhetoric we have. The key to strong rhetoric is using language, rules and structures that your audience can easily understand and use.

Chapter 6: Play with Structure | Page 139

Taxonomies can be sequential.

Sequence is the order in which something is experienced. Some sequences happen in a logical order, where the steps are outlined ahead of time.

Other sequences are more complex with alternative paths and variations based on the circumstances, preferences, or choices of the user or the system.

These are all examples of sequences:

- A software installation wizard

- New patient sign-up forms

- A refund process at a retail store

- A job application

- A recipe

- A fiction book

- The checkout process on a website

Like any taxonomy, the categories and labels you choose affect how clear a sequence is to use.

Chapter 7: Prepare to Adjust | Page 148

Adjustments are a part of reality.

From moment to moment, the directions we choose forever change the objects we make, the effects we see, and the experiences we have.

As we move towards our goals, things change and new insights become available. Things always change when we begin to understand what we couldn’t make sense of before. As a sensemaker, the most important skill you can learn is to adjust your course to accommodate new forces as you encounter them on your journey.

Don’t seek finalization. Trying to make something that will never change can be super frustrating. Sure, it’s work to move those boxes and arrows around as things change. But that is the work, not a reason to avoid making a plan. Taking in feedback from other people and continuously refining the pieces as well as the whole is what assures that something is “good.”

Don’t procrastinate. Messes only grow with time. You can easily make excuses and hold off on doing something until the conditions are right, or things seem stable.

Perfection isn’t possible, but progress is.

Chapter 7: Prepare to Adjust | Page 149

The sum is greater than its parts.

We need to understand the sum of a lot of pieces to make sense of what we have.

For example, let’s say we’re working on bringing a product to the market. To support this process, we might create:

- A hierarchical diagram of how the product is structured and labeled for users

- A flow diagram of the sequence users experience in the product

- A lexicon of terms the product will use, vetted to make sense to our audience

These are all important pieces individually, but we need to look at them together to answer questions about the whole such as:

Chapter 7: Prepare to Adjust | Page 151

Argue about discuss it until it’s clear.

It’s totally normal for fear, anxiety, and linguistic insecurity to get in the way of progress. Learning to work with others while they’re experiencing these not-so-pleasant realities is the hardest part of making sense of a mess.

Tension can lead to arguments. Arguments can cause resentment. Resentment can kill momentum. And when momentum stalls, messes grow larger and meaner.

To get through the tension, try to understand other people’s positions and perceptions: